Photos: Volker Kreidler, Interview: Sofia Bergmann

Volker Kreidler has specialized his photography in Eastern Europe for over 30 years. His most recent series, Border Areas, aims to capture how people near the Polish and Hungarian borders in Ukraine live. The project started in October 2021 through March 2022, just before the Russian invasion. He then managed to return in September 2022 and again in March this year, joined by his now-colleague Anastasiia Kuznietsova, a Ukrainian photographer who fled to Berlin.

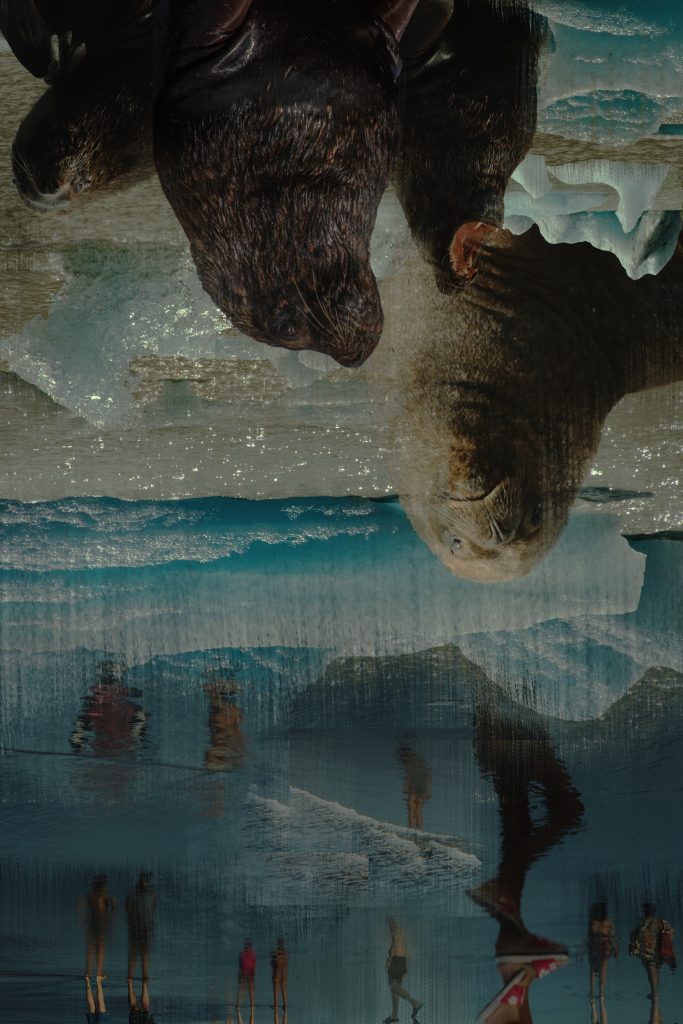

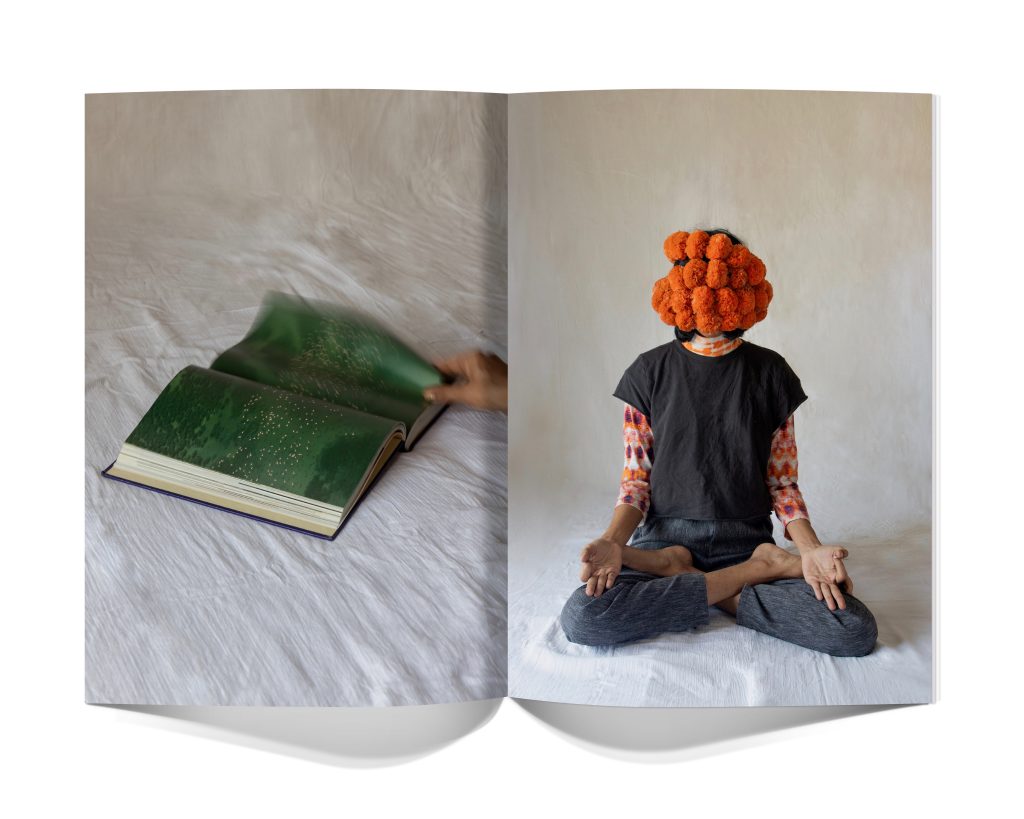

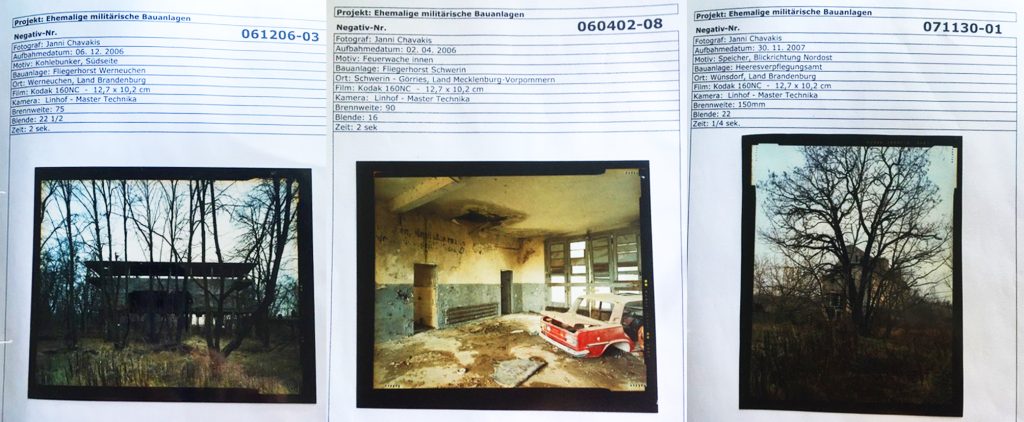

Kreidler’s photos are not sensational and do not depict a Ukraine which we see on the cover of newspapers. While some elements of the war shine through, his methods are centered around showing reality point-blank. A mixture of street and landscape photography from these regions, the series aims to visualize not only what these places look like, but the complex relationships between people and their surroundings and how they coexist.

For our second tIR Spotlight series, the Image Report sat down with Kreidler to chat about his work and Border Areas.

“You can’t just photograph around because everyone here is super nervous. They will think you are Russian spies and you don’t know who might have a gun in their basement.”

tIR: Can you first tell us about your journey to photography and what kinds of topics interested you most until now? What drew you to working so much in Eastern Europe?

Kreidler: I have been photographing for 140 years in principle – my father, grandfather and great-grandfather were all photographers. We have been doing this since 1860 and I’m not kidding when I say that I basically grew up in the photo lab. It was all about photography. There was only one photo shop in the Swabian Province, and my mother worked there while my father went around to photograph. I told myself that this is what I wanted to do because I found the medium so interesting. But I didn’t want to be an artist, rather, a photographer. I did an apprenticeship with my father which didn’t last long, so I spent most of my time in the early 80s in Stuttgart where I did a lot of commercial photography. Photographers would go down into these posh underground garages….those were the good days.

I realized that commercial photography was never enough so I enrolled in photo design in 1988 at the Fachhochschule Dortmund. That was the school to be at. Somehow, it was such an awakening experience for me.

As Germany unified in 1989, East Germany was for us photographers like some sort of movie. It was basically the same country, same language, but everything was just different. Of course we all wanted to photograph the former GDR, so I went to Dresden with a friend. We wanted to photograph 1930’s architecture, and I photographed the German Hygiene Museum. The director then told me ‘just stay here, we have an old studio in the Museum, about 600 square meters, it’s all yours.’ He later went to Kyiv in 1991 and came to me and said: ‘you have to go there, it’s absolutely absurd. We need to come up with a project for you to do there.’ So we immediately thought of Chernobyl…and I flew to Kyiv. That was my first Eastern European project, and I have basically stuck to it ever since.

Your most recent series Border Areas documented daily life in Ukrainian border cities before and during the ongoing war. How did this project unfold?

I have been doing similar things for the last 30 years, and it’s all about social topography. In other words, the interaction between city, man and society.

In principle, it’s all about a viewer and to transmit not what something looks like, but rather how such a system, how a country or a city functions. It’s all based on that – I transport, I don’t do any journalism. Border Areas was a project where several universities from different countries wanted to do a project together about people living in border areas in Ukraine, and what drives them. There were scientists who always did interviews in selected cities: two at the Polish-Ukrainian border, and two at the Ukrainian-Hungarian border.

And then you joined Anastasiia?

Exactly, Nastya [Anastasiia] is essentially a refugee and she now works with me. I insisted on bringing a Ukrainian photographer with me because I didn’t want to embody this typical Western European photographer who goes to Ukraine. I went back in September and I brought her with me.

What were some of the moments, emotions, places or people you encountered while photographing this series that you will never forget?

Nastya fled to Berlin about a week after the war started…she is normally very cool-headed but one meter into crossing the border into Ukraine [in September, 2022], she just broke down.

I was in Lviv and the whole city was full with soldiers and I was wondering why all these soldiers in battle uniforms were around 17, 18, 19 years old. An hour later they all got into a bus and slowly drove through the city….and everyone who stood around got on their knees. I still get goosebumps. There were so many situations, the first time I heard sirens I was laying in bed in the hotel.

And in that case, you would wake up and go to the basement, or just wait?

So I went down and they said: ‘Volker what’s wrong?’

‘The sirens!’ I said.

‘That’s no problem, go back to sleep!’

What did you learn from Border Areas that was different from previous projects?

The main difference is that the photos that I took were taken in a war context and that it sometimes also got dangerous to photograph. Nastya once got in a lot of trouble. They followed her in Uzhgorod and when she went to the supermarket, the police came and arrested both of us. They didn’t want to scare us, they simply said that you can’t just photograph around because everyone here is super nervous. They will think you are Russian spies and you don’t know who might have a gun in their basement.

Did that maybe change your role as a photographer a little bit?

No, I am always doing the same as before. You just have to be careful of course, it just has to do with respect. You have to behave in a way that doesn’t interfere with their sphere. You just have to work differently.

You photograph in a way that includes a lot of minor details, often shooting from a distance to capture surrounding elements. Can you tell us more about your photographic methods?

I come from a [Andreas] Gursky schooling. Back then, one strived to make big photos: maximal information, show all the reality. That has changed over the years. At the moment I am trying to get close, I used to never photograph people.

That also relates to what you meant before about showing daily life and not just war.

Right now there isn’t even war in those places. That was the problem: As I went to Ukraine the first time, everything was normal. The second time [in September 2022] the war had started, but in the places in western Ukraine where I was, there was no war. So I walked around a bit unsure, because I wanted to actually show a juxtaposition which just wasn’t there. It was almost better, because it was summer and everyone was outside and it was warm. And I thought, what should I photograph? I wanted to photograph bunkers, but that just became so cliché. So, I photographed what was there: daily life in the summertime.

What are some of your frustrations with photography today? What are some things you’re looking forward to in your work?

I am always working on about five or six projects, so soon I am flying to Athens and am doing a book project. Then I am doing a project about my family’s story and all the photographers in my family. I have over 400,000 glass slides from that time and I want to rework them somehow and try to recreate a reality from 100 years ago which no longer exists, with the help of AI.

Frustrations are always money. People never pay enough and it’s somehow laughable. You can be happy when just the travel costs are covered.