By the Image Report founder, Jannis Chavakis.

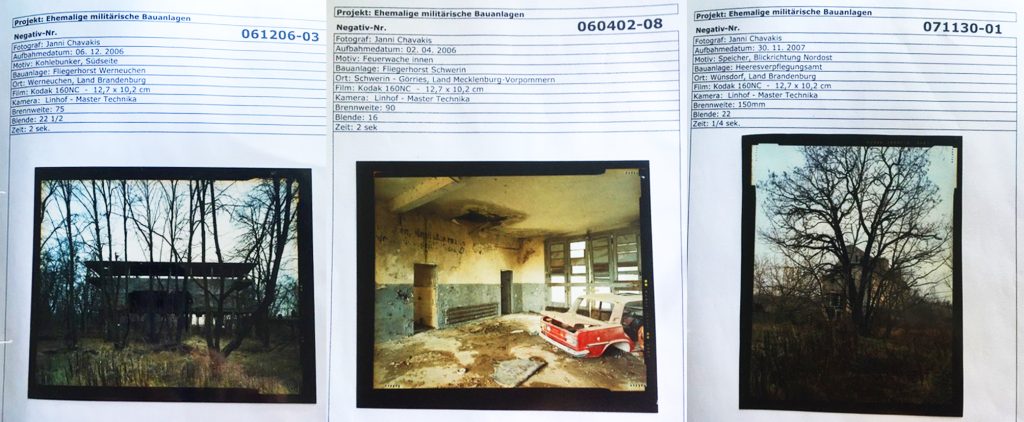

The photos in this first series for tIR Spotlight are dedicated to my friend and distinguished architecture photographer Robert Conrad, who recently passed away much too soon. For five years (2005-2010), we photographed some 70 former military installations in the five new German states during the fall and winter months. Neo-Baroque buildings of the Wilhelminian period, village-like Nazi barracks, socialist functional buildings of the postwar period — Robert had a plan. This plan convinced the Verwertungsgesellschaft Bild-Kunst (Art Collecting Society) in Bonn to finance the project for us. Robert knew these places, he had visited them all in the nineties several times. His secret paths led us to abandoned places and he was obsessed with detail, always wanting to learn the story behind the facades. What were their purposes, what materials were used, who was the architect — he knew everything. I just pressed the shutter button. Robert took the photos.

During the last decade of the 20th century a large number of properties, which had until then been used for military purposes, fell into the hands of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Federal states after the withdrawal of the allied forces. We photographed some of the almost endless surfaces, previously excluded from every public civilian sector. Construction plants and sites formerly kept under strict secrecy fell into the responsibilities of federal and communal city planning, along with state development constructions within only a few years after having been blank spots on the map.

Within the boundaries of the new federal states, the western group of the GUS troops, or rather the Soviet units of the People’s Army, left behind huge unexploited areas after the sites were dissolved and the troops withdrew. Due to the termination of military usage and the former secrecy, numerous structural bodies of evidence of the military apparatus of the German Empire, partially also the Weimar Republic, but most of all of the National Socialist [Nazi] State, and the Soviet GDR [East Germany], were made accessible to civilian recording, assessment and possible use.

“To this day, many of the areas have remained in a quasi-original state, still displaying a rich brew of historic and sociocultural authenticity due to the decades of hidden existence. Historic relics range from urban development designs to the still-existing interior decoration, awaiting their rediscovery and documentation.”

Not only do the sites consist of the technical military installations with the cleared out weapon depots, the workshops, the garages and hangars, but they also comprise of an overwhelming apparatus of administrative social buildings and housing: On the deserted barrack grounds we found men’s quarters, sports arenas, office buildings, theatre centers, military settlements with garden plots and high-rises in the socialist building style (Plattenbau). The spectrum of the newly discovered architecture ranges from the conservative historic-academic school of the German Empire in the style of ancient palatial structures, to modern absolutist styles of architecture, with concrete skeleton buildings, and Bauhaus elements as well as industrial slab, or flagstone buildings of the GDR (Plattenbaus). On the grounds of the new Federal States (Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Lower Pomerania) in particular, many typical military installations were erected at the time of the National Socialist armament policy.

Traditionally, these grounds were structurally weak and at that time strategically interesting for the Nazis to comply with the armament policy of the National Socialists. The military enjoyed high financial support for its constructions, which expressed itself also in its constructions and in the claim to use an especially “progressive architectural language.” To this end, and contrary to official state propaganda, construction departments also employed Bauhaus architects who created very modern architecture within the framework of the “blood and soil aesthetics”, which were oriented towards international standards, particularly Scandinavian and British. Among the architects who were employed by the National Socialist military were also well known planners such as Hans Poelzig who re-planned the “Scheunenviertel” in Berlin at the time of the Weimar Republic, Egon Eiermann who designed the plan for the reconstruction of the “Gedaechtniskirche” in Berlin, and Sergius Ruegenberg — later an exhibitor at the “Internationale Bauaustellung” in Berlin-Hansa neighborhood. Without a doubt, the main purpose of the military construction programme was to indoctrinate the soldiers and the civilian employees to make them obedient to the inhumane regime.

“Without a doubt, the main purpose of the military construction programme was to indoctrinate the soldiers and the civilian employees to make them obedient to the inhumane regime.”

After 1945, most of the grounds came into the possession of the Soviet army and later in-part to the People’s Army of the GDR, who used these areas for their many purposes. The grounds underwent certain architectural alterations which partially led to a deformation of architecture and city construction. Thereby, the existing grounds sometimes extended to further structural bodies of historic evidence of the occupation of Eastern Germany by the Soviets. To this day, many of the areas have remained in a quasi-original state, still displaying a rich brew of historic and sociocultural authenticity due to the decades of hidden existence. Historic relics range from urban development designs to the still-existing interior decoration, awaiting their rediscovery and documentation.

A systematic and scientific inspection and examination of these architectural ensembles had not occurred when these photos were taken, as such plants were generally seen as solely economic resources. People also shied away from occupying themselves with the architectural heritage of the Nazi-Regime and of the Soviet period. However, there has been profound comparable research in the field of architectural history by Prof. Dr. Winfried Nerdinger from the Technical University of Munich and by Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Schaeche from the Technical University in Berlin. Most notably, Prof. Dr. Karl-Heinz from the University of Potsdam conducted a thorough and commendable research project concerning the National Socialist settlement architecture.

Further studies on a federal scale on behalf of the authorities for monument preservation were restricted to an initial and incomplete inventory archive of the architectural stock. A number of separate buildings and ensembles were classified as historical monuments in the meantime, but have struggled to be upheld due to the continuing decay of the buildings, and an increasing regional economic stagnation and decreasing population in the five new federal states. On the economically attractive parts of the grounds, for example in proximity to cities, conversion programmes by the government have modernised some of the sites. Modernisation however, does not always mean that the sites are being preserved — it can also mean their loss and deconstruction.

For many of the properties, the hopes for a peaceful civilian and community use will unfortunately not come to fruition. In the context of demographic and economic developments through the shrinking of cities that are expected in Germany, an execution of new uses for the closed sites cannot be counted on. They are lacking investors and concepts. Meanwhile, the municipalities overtaxed by the upkeep of these ruins have turned to demolition of the historical sites, which are supported by the financial aid (and development) programmes of the European Union.

The sites will have likely vanished within a matter of years — their documentation is critical for the sake of architecture, history and learning from the past. While my partner in this project has passed away, our series aims to keep alive these bodies of 19th and 20th century important historical evidence for the future.

Note – Between 2005 and 2010 we exposed around 600 large format negatives with the aim of showing a traveling exhibition accompanied by a catalog to a large audience.